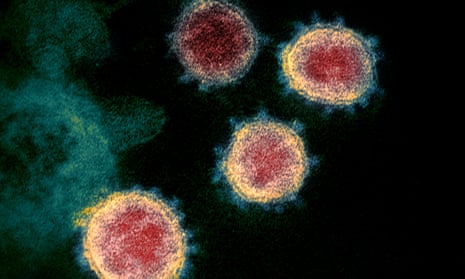

Viruses mutate all the time. Most of the new variants die out. Sometimes they spread without altering the virus’s behaviour. Very occasionally, they trigger dramatic changes.

And the question now facing scientists is straightforward: does variant VUI-202012/01 fall into this last category? Does it represent an increased health risk? Or has its recent rapid spread through southern England occurred because it has arisen in people who are infecting a lot of other people, possibly because they are ignoring Covid-19 restrictions?

These key questions, debated last week after health secretary Matt Hancock revealed the existence of the new variant, were answered firmly yesterday, by the government’s chief medical officer, Chris Whitty.

“As a result of the rapid spread of the new variant, preliminary modelling data and rapidly rising incidence rates in the south-east,” he announced, “the New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group (Nervtag) now considers that the new strain can spread more quickly. We have alerted the World Health Organization and are continuing to analyse the available data to improve our understanding.”

These analyses will involve scientists growing the new strain in laboratories, studying its antibody responses and testing its cross-reactions with Covid-19 vaccines. In addition, health officials are now carrying out random sequencing of samples from positive cases across the country in order to survey its spread through the nation and to build up regional maps of its prevalence. This will take at least two weeks.

The appearance of the new variant is alarming – though it should be noted that there have been several previous mutations of Covid-19. Last month, the Danish government culled millions of mink after it emerged that hundreds of Covid-19 cases were associated with Sars-CoV-2 variants carried by farmed mink. And in October, analyses suggested a coronavirus variant that originated in Spanish farm workers spread rapidly through Europe and accounted for most UK cases.

In neither case was it found that these variants increased transmission of the disease. However, it is now clear that this not the case for variant VUI-202012/01. What scientists must now tackle are concerns about the impact of the new variant – in particular whether it will lead to an increase in cases of severe Covid illness or actually result in fewer cases. The other big issue is whether the new variant will be able to bypass the protection offered by the Covid-19 vaccines now being administered across Britain.

“If the new variant was going to have a big impact on disease severity, we would have seen that by now,” said Ewan Birney, deputy director general of the European Molecular Biology Laboratory and joint director of its European Bioinformatics Institute in Cambridge.

“Hospital cases as a proportion of numbers of infections would have either rocketed or dropped dramatically. Neither has happened, so we can conclude that the impact on numbers of severe cases is likely to be modest: slightly more or slightly fewer.”

In addition, Birney said the vaccines have been tested with many variants of the virus circulating. “So there is every reason to think that the vaccines will still work against this new strain, though obviously that needs to be tested thoroughly.”

Exactly where the variant first appeared is not known. It may simply be that Britain’s extremely robust virus surveillance system spotted it before other nations did. “However, it is just as likely that the mutations that created this variant occurred in the UK and that is why we have seen it first,” added Birney.