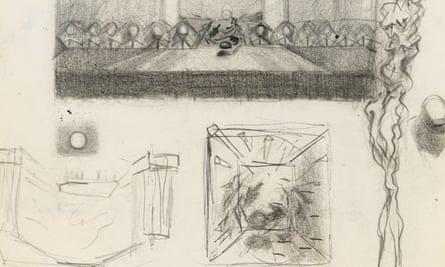

An early sketch for Salvador Dalí’s The Sacrament of the Last Supper reveals that the artist’s original thinking was far more conventional than the finished work would suggest. The painting, one of Dalí’s most popular, is a vast depiction of the Last Supper in which an ethereal torso with outstretched arms, possibly the resurrected Christ, looms over seated figures of Christ – portrayed with the features of the artist’s wife, Gala – and the apostles. The sketch reveals that Dalí’s original thinking was closer to Leonardo da Vinci’s interpretation of the event.

It is one of three Dalí drawings believed to be previously unpublished, each relating to his famous paintings of the mid-1950s, including Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus), in which he painted Gala as a devotional figure before a crucified Christ, and Skull of Zurbarán, his homage to the 17th-century Spanish master Francisco de Zurbarán.

“All three drawings are important in that they reveal the creative process of the artist,” art historian Jean-Pierre Isbouts told the Observer. “They reveal Dalí as a meticulous artist, contradicting his image as an exuberant surrealist who just paints whatever comes into his mind. He was very deliberate in his art.”

The Sacrament of the Last Supper, painted on a nine-foot-long canvas, was completed in 1955. It now hangs in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, where it is one of the most popular pictures with visitors. Its catalogue description notes that its background vista accurately portrays the view from Dalí’s home on the Catalan coast of north-eastern Spain, and that it was constructed according to complex mathematical ratios devised by Renaissance scientists and ancient Greek philosophers. Leonardo’s Last Supper, in the church and Dominican convent Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, features a landscape that recalls the nearby countryside.

In his early pencil study, Dalí depicted Christ at the centre of a long table, with his apostles arranged on either side of him, as in Leonardo’s masterpiece.

Isbouts, who has written books for National Geographic, said that it shows just how scrupulous Dalí was in working out a composition: “He even has a three-dimensional top-down view to see what that would look like … Sketches at the bottom of this study reveal Dalí’s mind at work as he looked for variations on the scene.”

He added: “It’s almost a copy of Leonardo’s Last Supper. Dalí’s ultimate composition is more nuanced. He moves some of the apostles forward, giving more scale and depth to the composition, and adds this looming nude torso. So you can see that, in his original thinking, it was a very conventional interpretation.”

Dalí made his name with depictions of subconscious imagery and dreamworlds in which ordinary objects are metamorphosed and distorted, most famously The Persistence of Memory, an eerie landscape with giant melting watches. He was an eccentric, larger-than-life character who said that every morning, he experienced “an exquisite joy – the joy of being Salvador Dalí”.

Comparing the study for Skull of Zurbarán with the final painting, Isbouts said: “Where the skull in the painting lacks a jaw with teeth, the study appears to suggest that there would be some indication of the skull’s teeth.”

The study for Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus) shows how he explored a depiction of the cross as a tesseract, a hypercube with eight cubical cells, which is thought to have been inspired by the work of the 16th-century Spanish mathematician and architect Juan de Herrera.

All three drawings are owned by Christopher Heath Brown, an American oral and maxillofacial surgeon, who has built up a vast collection of Dalí’s works on paper, worth $20m (£14.3m). They are included in a new book that he has co-authored with Isbouts, The Dalí Legacy: How an Eccentric Genius Changed the Art World and Created a Lasting Legacy, which will be published this month by Apollo Publishers.