- Our universe could be evolving the laws of physics all by itself.

- So say the authors of a new paper who believe the universe is autodidactic, or able to teach itself.

- If true, that would mean all of our existing laws of physics are subject to some higher-order universal laws that control this evolution.

An autodidact is someone who has learned a subject without a teacher or formal education. Famous examples of these self-taught maestros include Leonardo Da Vinci, master of 16 languages; Kató Lomb, a prolific Hungarian interpreter that knew at least 17 languages; and WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. Now, there may be a new entry on that list: the great cosmos. The universe could be constantly teaching itself how to evolve into a more stable state, according to new research that was recently published to the pre-print server arXiV (meaning the work has not yet been peer-reviewed).

The paper—authored by researchers at Microsoft and scientists at Brown University, among others—explains that all of the laws of physics we can see or measure today are laws that have worked themselves out over time. If we want to grasp how these laws of physics evolved, they say, we ought to apply Darwinian natural selection to cosmology.

Let us explain: As the universe sought stability over time, the simpler laws of physics it relied on in the beginning evolved to become much more sophisticated. Why are there still cats and dogs in our world, but no trilobites or dinosaurs? Cats and dogs proved best-adapted to their environment and successfully passed on their genes to their progeny. The same is true for the universe by analogy—the difference being that the universe doesn’t need to compete with other universes, but to keep going.

Picture an early version of the universe where, for instance, gravitational attraction between objects was a more primitive concept. In that case, Newton’s law of gravitation—which states that all particles of matter in the universe attract any other particles of matter with a force that is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers—could not be true yet. Today, that law explains why the moon’s surface gravity is about one-sixth as powerful as the gravity on Earth (the moon has far less mass). But in this simpler version of the universe, perhaps gravity was a more static concept, and gravity on the moon and Earth were the same. You can apply the same line of thinking to the other 14 laws of physics.

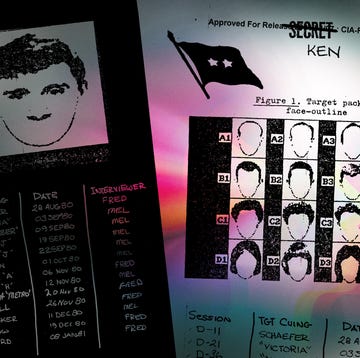

“Over time, that system will teach itself, and some fundamental laws will arise, and that's really what they're talking about [in the paper],” explains Janna Levin, a professor of physics and astronomy at Barnard College of Columbia University and director of sciences at Pioneer Works, a New York-based community encouraging radical thinking among the arts and sciences. “If the universe can compute with a given set of algorithms, then maybe it can do the same kind of thing we see in artificial intelligence, where you have self-learning systems that teach themselves new rules. And by rules, in cosmology we mean laws of physics.”

At this point, the paper mingles cosmology, or the study of the universe and its origins, with biology. “We ask whether there might be a mechanism woven into the fabric of the natural world, by means of which the universe could learn its laws,” the authors write. In other words, a universal law might transcend all scientific fields. That means that the laws of physics, as we know them, could be subject to higher-order laws of the universe that control them—and that we can't even comprehend.

“Exploring links between fields is crucial because knowledge is not fundamentally compartmentalized,” says Bruce Bassett, professor at the University of Cape Town’s Department of Mathematics and head of the Cosmology Group at the African Institute of Mathematical Sciences in South Africa. We humans are simply narrow-minded. “We segment and compress knowledge into biology, and physics, and sociology because of our limited brains, and the cost of that segmentation and compression is that we easily miss the commonalities and hidden universality between branches of human knowledge.”

That might be why humans have a hard time grasping the idea that the universe could be autodidactic—we can’t explain it well with our current scientific disciplines. “The universe is under no obligation to make sense to us,” renowned cosmologist Neil deGrasse Tyson has said.

And, unlike us humans, the universe does not need to compete with other universes; the cosmos is minding its own business. Of course, when we use verbs like “compete” and “mind” to describe the totality, we are succumbing to anthropocentrism, the philosophical viewpoint that everything starts and ends with humans. We can’t really help it though. “A lot of the way we think about the world is rooted in the language that we become familiar with,” Levin says. “The universe doesn’t have a conscious mind, just like selection hasn’t; selection is 100 percent agnostic.”

Toward the end of their nearly 80-page-long paper, the scientists admit that all they are doing is trying to take the first baby steps toward the formation of a new theory. “It is indeed early to comment about whether these ideas have anything to do with our universe. The core idea is intriguing and blends cosmology with the core ideas behind artificial intelligence, but is speculative and radical at the same time,” Bassett says.

He is quick to add that theoretical physics needs radical ideas, though. “It is an invitation to explore a crazy idea because we find ourselves confronted by a crazy universe,” he says. “Chances are, it will not lead anywhere interesting, but perhaps it will inspire a real breakthrough, and perhaps it will lead us somewhere even the authors could not imagine.”

Stav Dimitropoulos’s science writing has appeared online or in print for the BBC, Discover, Scientific American, Nature, Science, Runner’s World, The Daily Beast and others. Stav disrupted an athletic and academic career to become a journalist and get to know the world.