Seemingly 'empty' burial mound is hiding a 1,200-year-old Viking ship

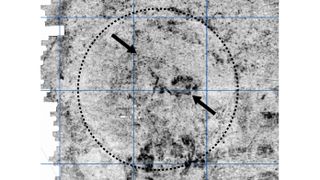

Ground-penetrating radar has revealed the outline of a Viking ship in a mound in southwest Norway that was once thought to be empty.

A Viking Age burial mound in Norway long thought to be empty actually holds an incredible artifact: the remains of a ship burial, according to a ground-penetrating radar analysis.

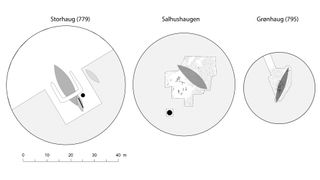

The remains, which are still underground, indicate that a ship burial took place during the late eighth century A.D., the very start of the Viking Age (A.D. 793 to 1066). If confirmed, it would be the third early Viking ship burial found in the area, on the coast of the island of Karmøy in southwestern Norway, a region that may be the origin of Viking culture.

"This is a very strategic point, where maritime traffic along the Norwegian coast was controlled," Håkon Reiersen, an archaeologist at the University of Stavanger in Norway, told Live Science. Reiersen works for the university's Museum of Archaeology and led the team that made the discovery last year, near the village of Avaldsnes.

Harald Fairhair, the legendary first king of Norway, lived in a royal manor there. Before that, the area was a center of political power from the Bronze Age (about 1700 B.C.) until the medieval period.

"This was an important place for 3,000 years," Reiersen said.

Related: Viking warriors sailed the seas with their pets, bone analysis finds

Viking burial

The Salhushaugen mound, where the ship-shaped signals have been detected, was first excavated in 1906 by the Norwegian archaeologist Haakon Shetelig. Shetelig had already discovered the nearby Grønhaug ship burial from A.D. 795, and co-directed the excavation of the famous Oseberg ship burial, from 834, in the southeastern part of Norway.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But he was disappointed to find only arrowheads and wooden spades in the Salhushaugen mound. (An earlier ship burial, the Storhaug ship from 779, was discovered by other archaeologists beneath yet another nearby mound in 1886.)

Reiersen suspects Shetelig's team stopped digging when they struck a rock layer near the bottom of the mound. If they had dug deeper, they might have found the Salhushaugen ship, which seems to be buried within the rock layer — a practice that's also been seen at other sites, Reiersen said.

The signals come from ground-penetrating radar equipment, which uses the reflections of pulses of radio waves to reveal objects buried up to 100 feet (30 meters) beneath the surface. They've revealed the impression of a ship about 65 feet (20 m) long.

That's larger than the 50 foot-long (15 m) wooden ship beneath the nearby Grønhaug mound, but slightly smaller than the more than 65-foot long (20 m) wooden ship beneath the nearby Storhaug mound.

The University of Stavanger team hopes to carry out further excavations of the Salhushaugen mound later this year; and the results of those will determine if they dig down to the ship.

"We're confident this lens-shaped signal actually comes from a ship," Reiersen said. "It shares the dimensions and size of previous ships, and it's situated in the middle of the mound. But we don't know how well preserved it is."

Mystery ship

There is also the possibility that the Salhushaugen mound, which doesn't seem to have been looted, may still contain artifacts like those found at the Storhaug mound, Reiersen said.

When the mounds were newly built, they would have been visible from ships entering the narrow Karmsund strait, between Karmøy and the mainland — the entrance to the vital sea route through the western islands known as the Nordvegen, which gives modern Norway its name, he said.

The new find fits a recognized pattern that ship burials were made in clusters, Jan Bill, an archaeologist at the University of Oslo and curator of the Viking Ship collection at the university's Museum of Cultural History, told Live Science. Bill is not involved with the new research.

Bill has found evidence from other excavations indicating that ship burials of Viking kings and chieftains were "staged" to seem to be on water, even though they were on land; for example, access to the ship during the burial was only via gangways.

This hints that their purpose was to suggest the buried king wasn't really dead but merely "sailing away" to be with his ancestors — a belief that predates the Vikings.

"I think these ship burials go back to a way of consolidating power among Germanic peoples," Bill said. "The idea was that the king was a descendant of a god, such as Odin or Wotan."

Editor's note: Updated at 12:02 p.m. EDT to fix the year of the first Salhuhaugan excavation from 1904 to the correct year of 1906. Also, to note that the Storhaug ship was not 88 feet (27 meters) long, but rather over 65 feet (20 m).

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.