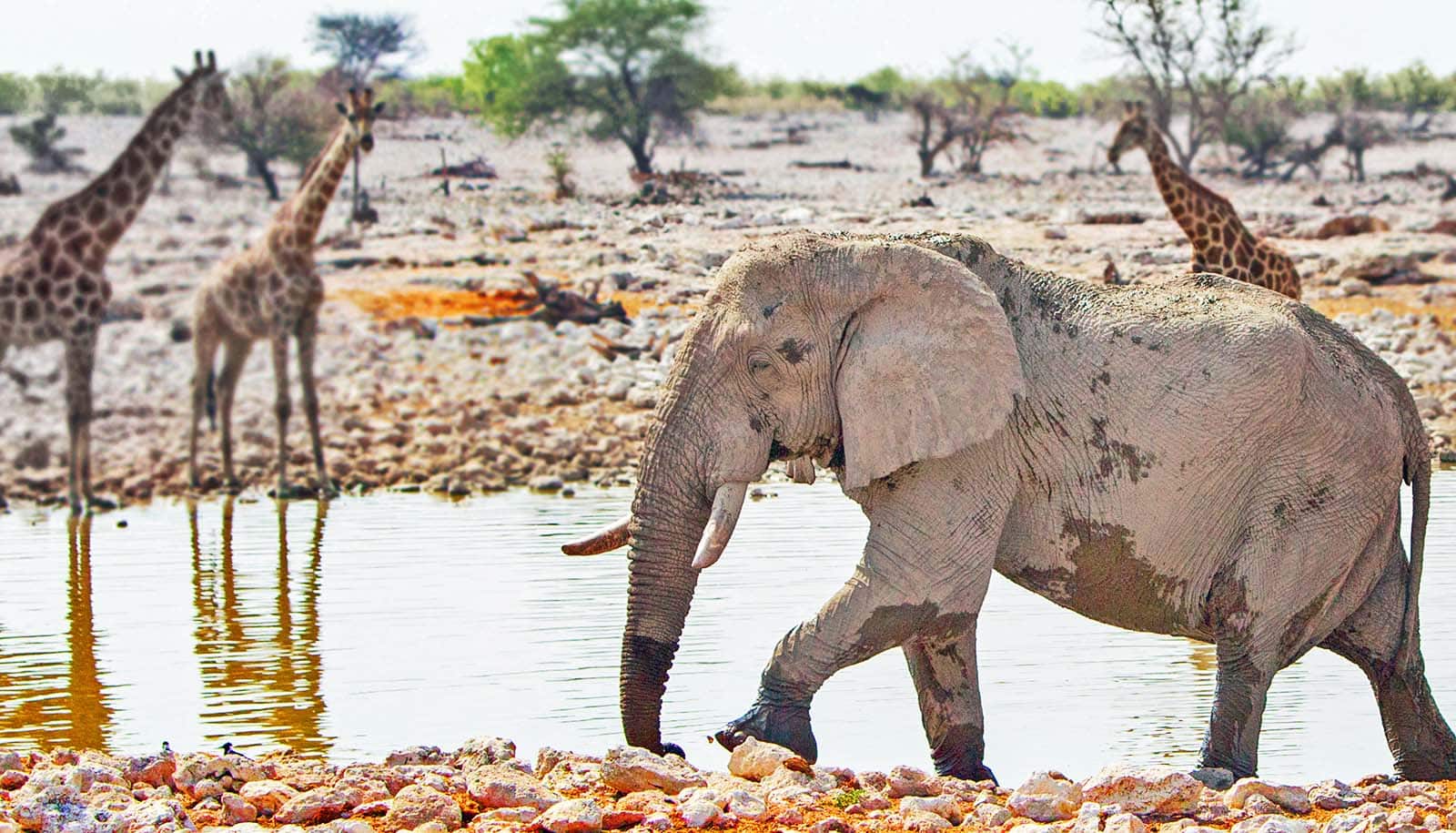

New research shows what the loss of land mammals has done to food webs over the past 130,000 years.

“While about 6% of land mammals have gone extinct in that time, we estimate that more than 50% of mammal food web links have disappeared,” says ecologist Evan Fricke, lead author of the study in Science. “And the mammals most likely to decline, both in the past and now, are key for mammal food web complexity.”

A food web contains all of the links between predators and their prey in a geographic area. Complex food webs are important for regulating populations in ways that allow more species to coexist, supporting ecosystem biodiversity and stability. But animal declines can degrade this complexity, undermining ecosystem resilience.

Although declines of mammals are a well-documented feature of the biodiversity crisis—with many mammals now extinct or persisting in a small portion of their historic geographic ranges—it hasn’t been clear how much those losses have degraded the world’s food webs.

To understand what has been lost from food webs linking land mammals, Fricke led a team of scientists in using machine learning to determine “who ate whom” from 130,000 years ago to today. Fricke conducted the research during a faculty fellowship at Rice University and is currently a research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Using data on modern-day observations of predator-prey interactions, Fricke and colleagues trained their machine learning algorithm to recognize how the traits of species influenced the likelihood that one species would prey on another. Once trained, the model could predict predator-prey interactions among pairs of species that haven’t been directly observed.

“This approach can tell us who eats whom today with 90% accuracy,” says Rice ecologist Lydia Beaudrot, the study’s senior author. “That is better than previous approaches have been able to do, and it enabled us to model predator-prey interactions for extinct species.”

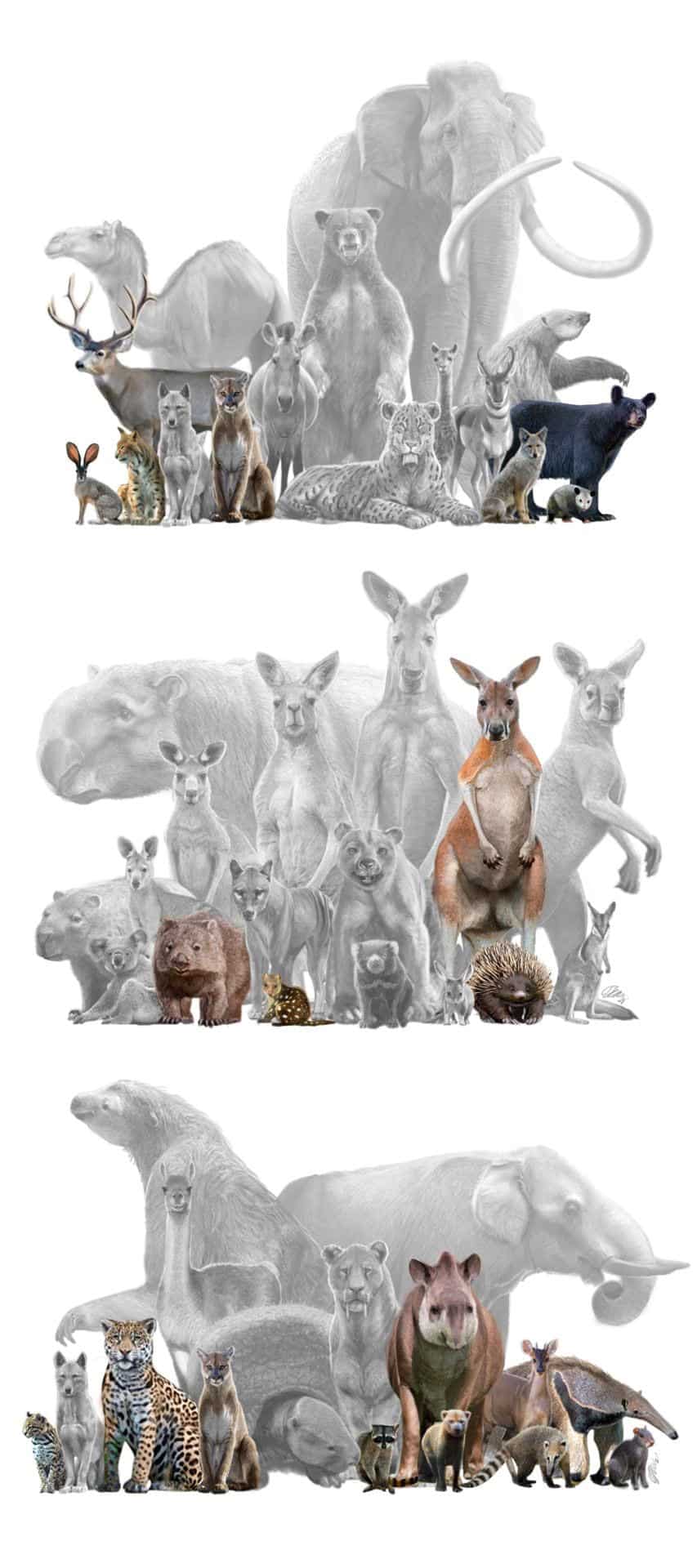

The research offers an unprecedented global view into the food web that linked ice age mammals, Fricke says, as well as what food webs would look like today if saber-toothed cats, giant ground sloths, marsupial lions, and wooly rhinos still roamed alongside surviving mammals.

“Although fossils can tell us where and when certain species lived, this modeling gives us a richer picture of how those species interacted with each other,” Beaudrot says.

By charting change in food webs over time, the analysis reveals that food webs worldwide are collapsing because of animal declines.

“The modeling showed that land mammal food webs have degraded much more than would be expected if random species had gone extinct,” Fricke says. “Rather than resilience under extinction pressure, these results show a slow-motion food web collapse caused by selective loss of species with central food web roles.”

The study also shows that all is not lost. While extinctions caused about half of the reported food web declines, the rest stemmed from contractions in the geographic ranges of existing species.

“Restoring those species to their historic ranges holds great potential to reverse these declines,” Fricke says.

He says efforts to recover native predator or prey species, such as the reintroduction of lynx in Colorado, European bison in Romania, and fishers in Washington state, are important for restoring food web complexity.

“When an animal disappears from an ecosystem, its loss reverberates across the web of connections that link all species in that ecosystem,” Fricke says. “Our work presents new tools for measuring what’s been lost, what more we stand to lose if endangered species go extinct and the ecological complexity we can restore through species recovery.”

Study coauthors are from the University of Sussex, the University of Washington, the University of Alcalá, the University at Albany, and Aarhus University.

The research had support from Rice University, the Villum Foundation, and the Independent Research Fund Denmark.

Source: Rice University