Carlo Rovelli on the meaning of time

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Among the most striking discoveries of modern physics — if not the most striking — is that, in nature, time works differently from the familiar intuition we have of it.

Time, for instance, is not uniform: it flows at a different speed depending on where you are and how you move. In the 2014 film Interstellar, the hero travels to the vicinity of a black hole. On his return to Earth, he finds his daughter older than himself: she is an elderly lady, he is still middle-aged.

This is not Hollywood fantasy, it is how the world truly works. The film’s scientific consultant Kip Thorne has since received the Nobel Prize in physics, for his role in detecting the gravitational waves emitted by merging black holes. He knows his topic. If we do not experience similar time distortions in our daily life, it is only because here on Earth they are too small for us to notice.

It is not the first time science has shown our intuitions to be mistaken. Science is constantly learning something new, and more often than not such learning means jettisoning wrong ideas. That is why science often clashes with common sense — our intuition wants Earth to be flat and still, and time to be the same everywhere. None of this is true.

Time is a mystery that has always troubled us, stirring deep emotions. Perhaps it is because, as Buddha put it, our difficulty in dealing with impermanence (or the passage of time) is at the root of our suffering. Hans Reichenbach, in one of the most lucid books on the matter, The Direction of Time, suggested that it might have been in order to escape from this anxiety that the Greek philosopher Parmenides denied time’s existence, Plato imagined a world of ideas outside it and Hegel spoke of the moment in which the spirit transcends temporality.

It may be because of this that we have imagined the existence of “eternity”, a world outside time that we imagine inhabited by gods, a God or immortal souls. Our deeply emotional attitude towards the subject may have contributed more to the construction of cathedrals of philosophy than logic or reason did. The opposite emotional attitude — the veneration of time by thinkers such as Heraclitus or Henri Bergson — has given rise to just as many philosophies but still not brought us much nearer to understanding its reality.

Physics helps us to penetrate some layers of the mystery. But our grasp of the world is shaped by the vast dialogue that involves the whole of our culture, from physics to philosophy, literature to the neuro-sciences. All these crafts may be needed here. Physics has conclusively shown that the temporal structure of the world is different from our perception of it. It has given us the hope of being able to study the nature of time free from our emotional fog.

But in advancing towards quantum theories of gravity with a temporal structure far removed from our intuition, we end up losing our own sense of time. Just as Copernicus, by studying the revolutions of the heavens, ended up understanding that it is us rather than the sky that turns, exploring the nature of time leads us to discover something about ourselves. Perhaps, ultimately, the emotional dimension of time is not the film of mist that prevents us from apprehending its nature objectively. Perhaps the emotion of time is precisely what time is for us.

The uniform nature of time is scarcely the only feature where our intuition has turned out to be mistaken. To everybody’s surprise, the difference between past and future fails to show up in the elementary equations that govern the physical world. But the discovery that has been the most disconcerting of all has been finding out that the notion of “present” does not make sense in the larger universe; it only makes sense in the vicinity of us slow human critters.

“Here-and-now” is a well-defined notion in science, but “now” on its own is not. Philosophers are struggling greatly with this discovery: if we call reality that which exists now, what is reality after we have realised that there isn’t a well-defined “now” all over the universe? The very grammar we use to talk about things, in which verbs have only a past, future and present tense, is inadequate to describe the ways of nature.

In physics, a great debate on the nature of physical time has developed in an arc spanning from Aristotle to Newton and from Newton to Einstein. Our understanding has repeatedly deepened in the course of this process. For Aristotle, time is just a way to count what happens, but it becomes an autonomous flowing variable for Newton and is then reinterpreted by Einstein as a feature of the gravitational field.

Einstein’s great theory, general relativity, keeps receiving spectacular empirical support — confirming such counter-intuitive predictions as black holes, expansion of the universe, time dilation, gravitational waves and more. These give strong credibility to Einstein’s picture and continue to rule out alternative conjectures. But there is certainly more to learn.

We do not yet know the fate of matter falling into the black holes we see in the sky, where Einstein’s theory says that time comes to an end. And the full complexity of what we perceive as the flow of time is not accounted for by general relativity alone: it involves quantum theory, thermodynamics and probably more, including neuroscience and the cognitive sciences.

My own work in science has been concentrated on the effort to understand how the quantum nature of the world affects space and time. There is not yet agreement on a solution; but there is a rather large consensus around the expectation that the concept of physical time is likely to move even further away from our intuition, when its quantum properties are taken into account.

This is why reflecting on the nature of time is a constant concern for myself and many of my colleagues. Tentative theories of quantum spacetime have little that resembles time as we experience it. The basic equations of the theory on which I work, loop quantum gravity, have no special “time” variable at all. They describe processes in which things change but no single time variable can track all possible changes.

Does all this suggest our perception of time is illusory? It does not. But it indicates that what we perceive as time may not be a simple and elementary aspect of nature, but rather a complex phenomenon with many layers, each needing to be addressed by a different chapter of science. This is the true question about the nature of time: which aspects of our sense of it pertain to which domain of science?

Key aspects of time are described by the science of heat, thermodynamics. Any time the future is definitely distinguishable from the past, there is something like heat involved. Thermodynamics traces the direction of time to something called the “low entropy of the past”, a still mysterious phenomenon on which discussions rage. I have studied the hypothesis that some aspects of the solution might come from recognising a perspectival aspect for time. Think of the magnificent spectacle of the daily rotation of the sky: we see the sun, moon and stars, the entire cosmos, majestically rotating. It has taken millennia for us to understand why. To figure this out, we had to consider ourselves. It is not the vast cosmos that is rotating, it is we who live on a spinning rock. This is a perspectival explanation. Something similarly perspectival, I think, underpins our peculiar perception of the flow of time.

Entropy growth orients time and permits the existence of traces of the past, and these permit the possibility of memories, which hold together our sense of identity. I suspect that what we call the “flowing” of time has to be understood by studying the structure of our brain rather than by studying physics: evolution has shaped our brain into a machine that feeds off memory in order to anticipate the future. This is what we are listening to when we listen to the passing of time. Understanding the “flowing” of time is therefore something that may pertain to neuroscience more than to fundamental physics. Searching for the explanation of the feeling of flow in physics might be a mistake.

Our understanding depends on the neural structures shaped by the peculiar environment in which we live. They capture a very imprecise version of the actual temporal structure of reality. Our experience is an approximation of an approximation of a description of the world from our particular perspective as beings dependent on the growth of entropy, anchored to the thermodynamical arrow of time. For us, there is, as Ecclesiastes has it, a time to be born and a time to die. The time we experience is a multilayered, complex concept with distinct properties rooted in distinct layers of reality. Many parts of the full story are still far from being clear. Time remains, to a large extent, a mystery, perhaps the greatest one. A mystery that relates to issues ranging from the fate of black holes to the enigma of our individual identity and consciousness.

Will we be able to understand things better in the future? I think so. Our understanding of nature has increased vertiginously over the course of the centuries, and we are continuing to learn. We are glimpsing something about the mystery of time. We can see the world described by quantum theories of gravity: we can perceive with the mind’s eye the profound structure of the world where time as we know it no longer exists — just as Paul McCartney’s “Fool on the Hill” sees the world spinning round when he sees the sun going down.

I also think we are beginning to see that we are time. We are this clearing opened by the traces of memory inside the connections between our neurons. We are memory. We are nostalgia. We are longing for a future that will not come. Horace, the greatest poet of Roman antiquity and perhaps the greatest cantor of time, calls it our “brief circle” (“You must be wise. Pour the wine/and enclose in this brief circle/your long-cherished hope”). This clearing, opened up for us by memory and anticipation, is our time: a source of anguish on occasion, but in the end the marvellous gift of our existence.

Carlo Rovelli is director of the quantum gravity research group at the Centre for Theoretical Physics at Aix-Marseille University. His book ‘The Order of Time’ is published by Allen Lane on April 26

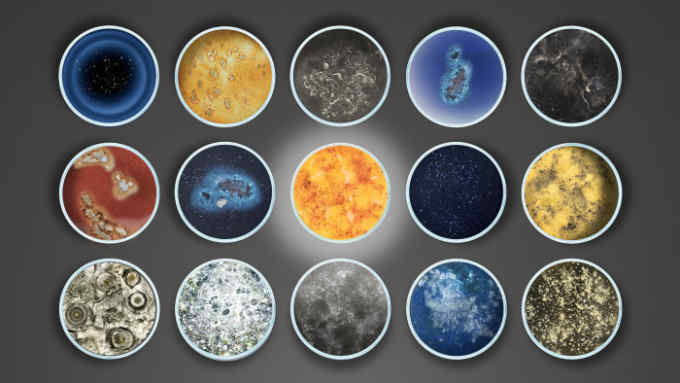

Photographs by Caleb Charland

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

To end our Masters of Science series, Carlo Rovelli will talk to FT science editor Clive Cookson on FT Facebook Live from 11.30am on Wednesday April 25. Watch (and ask questions) on facebook.com/financialtimes

For previous articles in the series, visit ft.com/mastersofscience

Comments